Russian Smokejumpers

Alexander Selin, the head of central Siberia's aerial firefighting force, is a man who knows how to make himself clear, even in English, a language he barely knows. The police, he tells us, are "garbage." Vodka is "gasoline." His driver? A "Russian barbarian." And caution, well, caution doesn't seem to be part of his vocabulary. Caution is for sissies and Americans. "No seat belts in Russia!" Alex barks as we speed away from a police checkpoint soon after our arrival in Krasnoyarsk, he and his driver unbuckling their belts in defiant unison.

After a few days in his care we will come to call Alex, simply, Big Boss. A thick-fingered, barrel-chested Siberian who hurls his words like shot-put balls, Alex rules a fiefdom the size of Texas with an army not much bigger than the Texas A&M marching band. His 500 smokejumpers, firefighters who jump from planes and rappel from helicopters, cover a swath of boreal forest that stretches from Arctic tundra to the Mongolian border.

Photographer Mark Thiessen and I have come to Siberia to see Alex's men in action, but by the time we're halfway from Krasnoyarsk to Shushenskoye, 200 miles (322 kilometers) to the south, I'm not sure we'll live long enough to see a single. We're throttling through the mountains in a pair of fume-filled Volgas, taking curves at 90 miles an hour (145 kilometers an hour), passing blind on hillcrests, narrowly avoiding one head-on collision after another—and I'm thinking wistfully back to our training in British Columbia, where Mark and I rappelled out of helicopters feeling as safe as the day we were born. Finally the lead car in our little caravan sideswipes a truck. We pull over to check the damage—a dented quarter panel—but the collective response is a shrug and a return to the road, full speed ahead.

So I'm not surprised the next morning when we board our first Mi-8, an 18-wheeler of a helicopter that is Russia's aerial firefighting workhorse, and there are no seat belts in sight—and practically no seats. Alex has taken our visit as an opportunity to host a half dozen cronies on a weekend fishing trip in the mountains, and when we land in a field to pick them up, gear gets piled willy-nilly between the two huge fuel tanks—a rubber boat here, an outboard motor there—and everyone plops down on whatever looks most comfortable.

That afternoon, over vodka shots at the fishing camp, Alex explains the Russian way of doing things. He's been to California and Idaho to see how American firefighters work, and when he thinks of riding in their helicopters—all strapped in by seat belts and regulations—he laughs at the memory. "No move, no speak!" he says. You can't size up a fire if you can't move around and look at it! You can't make a plan if everyone has to be quiet!

"And they call Russians crazy!" the pilot cuts in.

Having barely survived their driving, I'd say "crazy" seems about right, but you've got to be at least a little crazy to jump from a plane into a fire, and the Russians have been doing it longer than anybody.

"The idea of actually parachuting into fires was a Soviet invention," I am later told by Stephen Pyne, an American wildfire historian who is one of the few people outside Russia who know much about Avialesookhrana, Russia's aerial firefighting organization. "In the 1930s these guys would climb out onto the wing of a plane, jump off, land in the nearest village, and rally the villagers to go fight the fire."

Last year Avialesookhrana celebrated the 70th anniversary of its first flight. (It would have been the 75th anniversary, but when the first plane took off from Leningrad in 1926 to look for fires, the pilot made a beeline for Estonia and defected.) Once they got going, the Soviets quickly built a program that remains to this day the largest in the world—despite a decade of post-Soviet budget cuts that have halved the ranks, from 8,000 firefighters to 4,000.

It's a shoestring operation—just $32 million a year to cover 11 time zones, less than the United States might spend in a few days of a heavy wildfire season. But with their mismatched uniforms and 50-year-old biplanes, Russian smokejumpers do what their countrymen do so well: make do with less. Less money, less equipment, and yes, less caution—even with fire.

When we break camp the next day to return to Shushenskoye, I'm surprised to see that the campfire is left smoldering. It's a hot July day, which would be bad enough without the helicopter's rotor wash blowing everything all over the place, but the risk doesn't even seem to register with Alex, central Siberia's most powerful firefighting official. In the U.S., firefighters would douse a fire on an ice floe in the dead of winter, especially with journalists around. But here they play the odds the way they see them, and perfect safety is burdensome and unnecessary. Fire shelters and fireproof clothing? Too expensive, but that's OK, because the odds of needing them are low. Seat belts? Impractical. Thousands of times you will buckle and unbuckle, and probably for nothing. Campfire? It's not going anywhere.

Not surprisingly, people cause two-thirds of Russia's 20,000 to 35,000 annual wildfires—and by the time we've been in Siberia for a week, I find myself wishing they'd cause a few more. The Shushenskoye area is hot and dry but fireless, and after seemingly endless rounds of vodka-steeped hospitality we finally persuade Alex to send us north to Yeniseysk, where we hear fires are burning across the region.

When we get to the base in the town of Yeniseysk two nights later with our guides, firefighters Valeriy Korotkov and Vladimir Drobakhin, we're eager to finally get to a fire, and the gods respond accordingly: In the morning it is raining. Pouring. I look at Valeriy. "I thought you said Friday the 13th was your lucky day."

"Ahh, the day is not over, my friend."

Valeriy is one of those guys with so much heart that you believe in his luck. A smokejumper the past 25 of his 45 years, he smokes constantly (filtered cigarettes, "because I care about my health") and drinks lustily, but he never seems to lose the bounce in his step and rarely complains— even when he loses the last of his upper front teeth, which we suspect happened sometime during our month together. With a wavy shock of hair, salt-and-pepper goatee, and a suit of camouflage pasted onto his body by days of sweat, he exudes an intensity that seems a bit out of place when we find ourselves in civilization, like some sort of deep-cover soldier back from the front lines.

Midday the word comes: Hurry and get your stuff together, we're going to a fire. I'm just this side of incredulous, given that we've been socked in by rain for 12 hours, but a two-hour helicopter ride later, we land at the edge of a smoldering patch of forest and the sun is shining. Valeriy's lucky day! He and Vladimir quickly chop down some birch saplings to make poles for our canvas tent, and we hike what looks like an old logging road through a blackened forest to the fire line.

Twelve smokejumpers have been on this 120-acre (49-hectare) fire for nearly a week. It seems all but dead on this flank, but the guys chop a few saplings to make handles for their rakes and shovel blades and get to work, scraping clean a foot-wide swath of forest floor, then lighting a backfire with pine needles and birch bark. The backfire burns toward the wildfire, consumes its fuel, and stops it in its tracks—the basic technique of wildfire fighting everywhere, whether done with shovels and pine needles or bulldozers and drip torches.

Each summer Avialesookhrana's firefighters face the Herculean task of containing fires across 2 billion acres (800 million hectares) of the largest coniferous forest in the world. Though regional forestry offices help fight fires in more populated areas, smokejumpers—housed in 340 bases across the country—are the sole defense for half of Russia's territory, flying to fires in crews of five or six when parachuting from An-2 biplanes and in groups of up to 20 when rappelling from the Mi-8 helicopters.

"We face danger three times: one when we fly on plane; two when we jump; three when we go to fire," Valeriy says, and the statistics bear him out. In the past three decades 40 Avialesookhrana firefighters have died on the job—24 while fighting fires, 11 while parachuting, four in aircraft accidents, and one by lightning. Valeriy and Vladimir both tell me stories of parachuting fatalities, one when a jumper landed in water and drowned, another when a jumper hit an electric line. But jumping is the thrill that gets them hooked. "Two minutes fly like eagle, three days dig like mole," Valeriy says of the smokejumper's life—and the flying's worth the digging.

The day is late, so after making a couple hundred feet of fire line the guys break for a smoke. Everyone smokes unfiltered Primas—loosely rolled butts that cost about a nickel a pack and make health-conscious chain-smokers like Valeriy shudder. As we swap Russian and English swear words and laugh, Alexi Tishin, an earnest 28-year-old with a week of stubble and a smattering of gold teeth, says, "This is the best job for tough guys"—you get to jump out of planes, fight fires, live in the forest. He says he especially loves jumping to small fires and trying to put them out fast. If they kill the fire in a day or two, they get a few extra dollars each—no small sum, given that smokejumpers earn on average 3,100 rubles, about a hundred dollars, a month. The incentive seems to work: More than half of all fires are put out within two days.

The smokejumpers are true woodsmen—hunting, fishing, and trapping sable in the off-season to make ends meet, as nimble with an ax and knife as they are with their hands. When they land at a fire and make camp, they don't just make tent poles and shovel handles from saplings, they make tables, benches, shelves—you name it. I'm amazed to see one guy make a watertight mug out of birch bark.

It's a good thing their outdoor skills are solid, because their equipment often isn't. When we return from the fire line, Valeriy discovers that one of his brand-new experimental smokejumper boots has melted. The rubber sole is a mash of black goo. His boots lasted "an hour, at best" he says angrily, before launching into a torrent of complaint about poor Russian equipment. "This tent like from Second World War," he says, pointing at the canvas tent that will welcome mosquitoes and rain into our lives for days to come. The tents have no mosquito netting, the chain saws are heavy and unwieldy, the backpacks have no waist straps, the pull-on boots are made of cheap synthetic leather (and feet must be wrapped in towels to make them fit), the clothing is neither fire retardant nor water resistant. And everything is heavy.

For most of these guys that's just the way it is, but Valeriy and Vladimir are among the 120 Russian firefighters and managers who have been to the United States through an exchange program that began in 1993 between Avialesookhrana and the U.S. Forest Service. American and Russian exchangers alike are struck by the Americans' superior equipment and the Russians' inimitable resourcefulness.

Vladimir, who fills his American fireproof clothing with the stocky build of a linebacker, came home from a summer in the States with boots and tools and a wad of cash that was many times his annual pay, but he also returned with a new appreciation of his Russian brothers. "Put us in the woods with matches and a fishing rod, and we can live," Vladimir says. "We know how to eat mushrooms, catch fish, make a snare for animals. But for American firefighters, it would be a very bad situation."

Valeriy tells me how one time his squad's food was lost when it landed in the middle of a lake. They didn't have fishing gear, so he made a fishhook from a piece of metal on his reserve chute, pulled string from his parachute bag, cut a birch branch, and—voilà—they had fish.

By morning the rain we escaped in Yeniseysk has caught up with us, and we huddle under a tarp as we listen to the daily radio dispatch. A group of firefighters is stuck in the forest 200 miles (322 kilometers) to the northwest. There's no fuel to either fly them out or fly food in, so the dispatcher suggests that they build a raft and float down the river. No, they say, there's no good wood here for a raft. Then you'll have to walk, they're told—12 to 15 miles (19 to 24 kilometers) out, with all their heavy gear. You can almost hear the groans.

Fuel—or the lack of it—is a perennial problem for Avialesookhrana, even more the firefighter's bane than lousy equipment. Because we have a short time to see firefighters at work, Mark and I have been getting special treatment with helicopter transportation. But at the next fire, our luck runs out, and we get a taste of what smokejumpers have to put up with.

The first night there we're drenched by the same weather system we've been fleeing since we got to the Yeniseysk region. After two nights and a day of rain, the sky clears, and we brave the mosquito hordes to dry our stuff and wait in vain for the helicopter. The day after that, still no helicopter. We're later told that someone back at the base forgot to fill out the correct paperwork—and the camp's radio battery has died, so we can't even call in a reminder.

"Every time we have same problem," Valeriy says. "After rain, they think, 'Guys sit in forest? It's OK.'" Once he had to wait 15 days for a pickup.

When the helicopter finally comes, we've been in Siberia for nearly three weeks, we've seen a grand total of 45 minutes of very sleepy fire, and we're told that it snowed two inches in Yeniseysk that morning.

It's the middle of July, and it has been the wettest fire season here in 15 years. We decide to leave for Vladimir's region in northwest Russia, where it's hot and dry and fires are breaking out all over the place.

Vladimir's base in Syktyvkar, a city of 226,000 roughly 600 miles (970 kilometers) northeast of Moscow, is much like the one in Yeniseysk—a central building with offices and training facilities, plus a dormitory where the smokejumpers live during fire season, from late spring to early fall. The forest in this region is much more populated than what we've seen in Siberia, spotted with clear-cut logging operations that make it easier for local foresters to get to fires with bulldozers and local manpower.

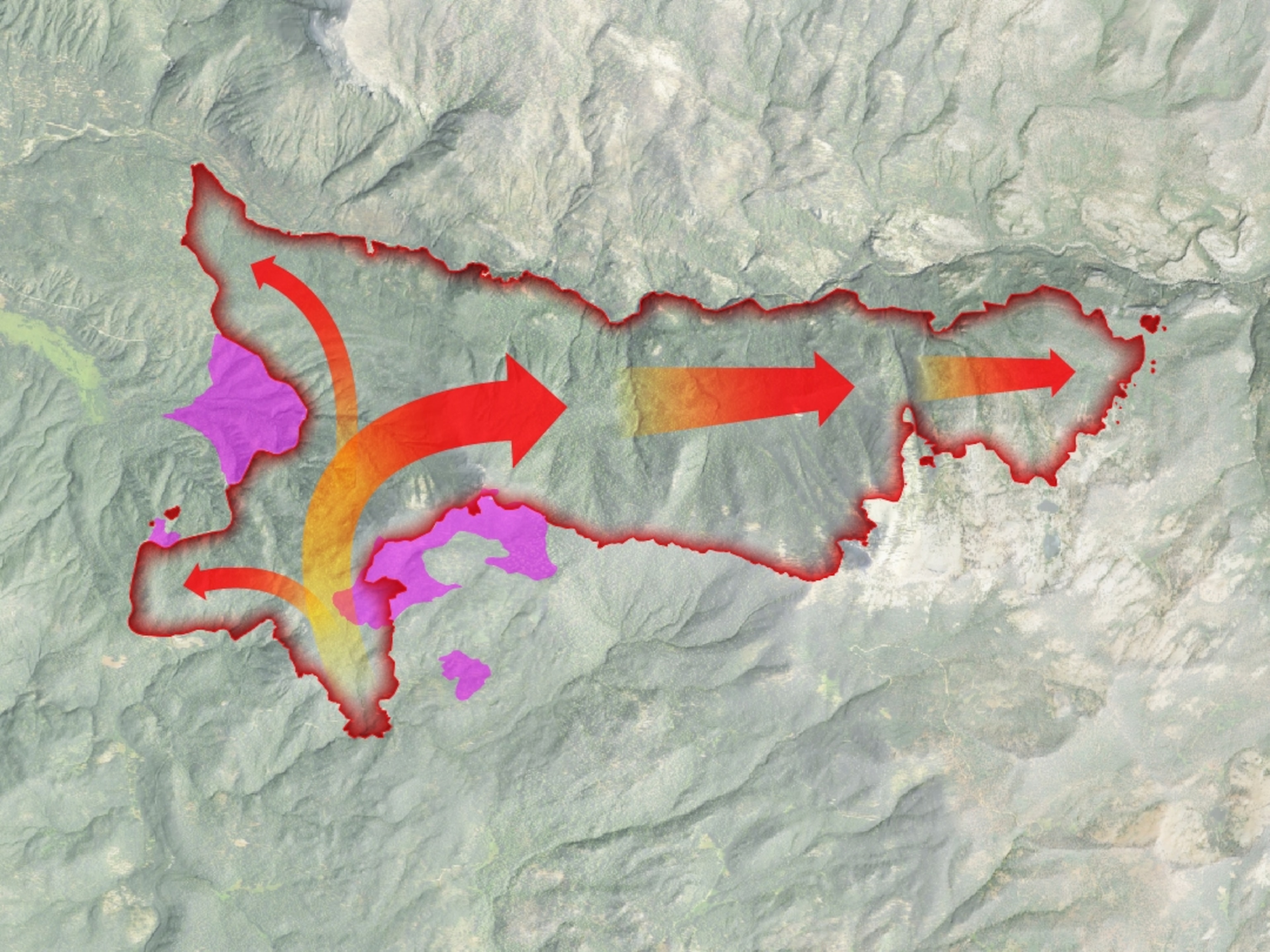

As we fly over the checkered terrain in an Mi-8, we pass a number of smoke plumes before landing near a square-mile (2.6-square-kilometer) fire that horseshoes around a boggy meadow. A crew of five smokejumpers is already camped in the middle of the meadow, and less than a mile (1.6 kilometers) away local forestry folks are cutting line in the forest with bulldozers. Shortly after we land, an An-2 biplane circles the fire and drops a hand-drawn map into our camp, and we hike west through the woods to stop one edge of the fire.

The fire is a slowly moving wall of flame a foot or two (0.3-0.6 meters) high, occasionally crowning into brush and treetops in quick whooshes of flame. The guys light a backfire with pieces of birch bark, and as the backfire burns forward to meet the fire, they extinguish its back edge with devices called "piss pumps"—shoulder-strapped rubber bladders that spray water through a nozzle. The backfire itself isn't even necessary after a point, and they take to knocking down the flames of the wildfire with spruce boughs, Vladimir leading the way. I catch the bug and see how much of the fire I can contain just by stomping on it with my boots. I take out a good 30 feet (9 meters) in a few minutes, and it's surprisingly satisfying. I have changed the course of nature.

Valeriy smiles at me and nods. Now I understand his job. "This is the best!" he says. "We work in this forest no for money. We work for our happiness. Not like people in Moscow."

The next day's firefighting isn't quite so much fun. When we return to the fire line in the morning, a dozer has savaged the forest floor, cutting the soil down to its sandy base in a 12-foot (4-meter) swath of toppled trees. We spend the rest of the day following the dozers as they knock down 80-foot (24-meter) trees and leave two-foot-deep (0.6-meter deep) trenches in their wake. As the smokejumper crew and a host of locals set a backfire from the dozer trench, the six-foot (two-meter) flames from the downed trees and brush are so much bigger than the foot-high wildfire that three times in the course of the afternoon a helicopter will mistakenly drop water on the backfire instead of the wildfire. "Overkill?" I ask Vladimir. He nods.

This type of firefighting is unusual for Avialesookhrana. Smokejumpers are initial attack firefighters. They jump on new fires in remote places and put them out as fast as they can. This—with the bulldozers, the inexperienced locals, the water drops—is more like a circus.

After seeing how much more damage the bulldozer did to the forest than the fire itself would have done, I ask Vladimir whether he thinks all fires need to be fought, or if some should be allowed to take their natural course. "Fires are natural, but bosses don't understand about letting fires burn," Vladimir says. He screws his face to one side and puffs out his chest like he always does when he imitates bosses. "They say, 'Every fire we have to put out, because it's dangerous.'"

In truth, they don't put out every fire, but that's only because they can't. In Siberia's remote expanses, where fire control would be prohibitively expensive, fires are allowed to burn. "Not being able to reach all these fires is probably for the good," says wildfire expert Stephen Pyne. "Fire is very much a part of the boreal ecosystem."

Fire has also been historically integral to human settlement in the Russian taiga. Hunters, trappers, foragers, and farmers all used fire to create habitable zones in the dense woods. Under communism, however, fire—whether of natural or man-made causes—came to represent an untamed threat to centralized control. "In the Stalin era, one was not allowed to waste resources," Pyne says. "There was a real sense that letting fires go was deviant, slacker, anti-Soviet behavior. So to suggest that maybe the thing to do is stand back goes against a lot of cultural and political habits that are very hard to break."

It also wouldn't be in Avialesookhrana's best interest. Already hamstrung by budget cuts, it's an organization that needs to prove its worth to survive, and firefighting heroics—not nuanced discussions of forest health and controlled burns—have so far been the best way to do that. In 1972, when wildfires of millennial proportions closed in on Moscow, 1,100 Siberian smokejumpers flew in to save the day. As Pyne writes in his book Vestal Fire, "Avialesookhrana glowed with pride. The periphery had literally saved the center. A grateful (and frightened) center replied with a major investment of rubles." Similarly, severe fires around Moscow in 1992 reminded government budget cutters of Avialesookhrana's value as an essential defender of Mother Russia.

When we fly to our last fire, we're accompanied by Yevgheny Shuktomov, the deputy chief of science and technology from Avialesookhrana headquarters near Moscow. Wearing American firefighting clothes from his exchange stint, he has brought three backpack firefighting units that use compressed air to shoot foam through a gunlike nozzle. Though they're designed for city firefighting, the minister of the department that oversees Avialesookhrana has bought five of them—at a staggering five grand a pop—to see how they work on wildfires. Yevgheny is here to test them.

When we land, the smokejumpers immediately set camp and go after the fire. It's the same kind of low-level ground fire we've seen before, and they beat it down with spruce boughs and dig sand from the ground to contain its edge. They work fast, breaking a heavy sweat in the cool evening, and stop only when they're told to save some fire line for the three guys with the special equipment. As a light rain begins to fall, Yevgheny and his crew come marching down the line, wielding their nozzles like commandos. It looks impressive, but they spray embers all over the place and the compressed air lasts only 45 seconds—so there's a lot of walking back and forth to the air compressor to reload. Valeriy, who has been assigned to photograph the affair, shakes his head. "Big bosses, like Arnold Schwarzenegger," he says, making a machine gun motion. "This only for picture. Piss pump and shovel—this is all you need."

The next morning, the only stretch of fire line that didn't hold was the part attacked with the spray guns; there the fire reignited and crept forward in spots until stopped by the rain. Turns out the shovels and sand worked much better. Back at our boggy camp, Yevgheny admits that the special units aren't very practical—too expensive and time-consuming. They'll keep them though. "Good for showing at some exhibitions," he says, smiling, and I'm reminded of Avialesookhrana's brochures and website photos, which show brightly uniformed firefighters with similarly improbable equipment.

"You need to go to America speaking English like that," one of the smokejumpers yells out to razz Yevgheny, and the guys around the fire laugh. They're playing a card game called "goat," an insult that'll get you killed in prison, I'm told, and they play it with vigor, slamming down their cards with each play. When he wins a game, Sergei Mykhyn, the tough, sinewy squad boss, makes profane pumping motions and calls his defeated opponent "milk brother," which I assume is somewhere just short of "goat."

Shirtless and tattooed, with fierce eyes and a cigarette-scorched voice, Sergei isn't the kind of guy who gets chosen to go to America. He's just too much Russian smokejumper. As we sit waiting for our ride out, the radio crackles to life, and it's bad news: The helicopter's rained in. Sergei looks over at us, the soft Americans and the soft bosses, with our fancy equipment and special treatment.

"Maybe you sleep in the swamp three more days," he says. Everybody laughs. We all know the truth—that the fireproof clothes, Gore-Tex raingear, and $5,000 spray guns can't keep nature at bay any better than a tattooed Russian with a handmade shovel.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest